Shannon O’Donnell

Petra, Jordan

Petra; A rose-red city half as old as time; though these words sound like the opening lyrics to a love song, they’re instead penned by a poet and speak of an ancient civilization that carved evidence of their history deep into the soft sandstone rocks jutting into the wide Jordanian skies.

Wandering through the miles of sandy roads, the nubby domes of eroded mountains visible in every direction; I was overwhelmed the moment I stepped into this ancient civilization.

How did they do it?

Why did they carve such beautiful structures into the side of the towering rocks?

And I wondered even more: since sandstone is so delicate, why is the evidence still here a full two thousand years later?

Petra’s history and the romantic edifices carved into pink rock piqued my curiosity long before we arrived. Those questions though, formed an ambiguous web of responses depending on who was asked to provide more details. Ask a historian and he’ll point you to ancient religious texts and the scarce written accounts that still exist from philosophers of the time.

The archaeologists will point to their excavations and aerial imaging that maps out the remnants of a city still buried under sand. And the mythologist? Well, he instead gathers stories, legends; the tales passed down through time and shaped throughout history to weave a complex possibility of the whys behind Petra.

when I traveled through Petra, I had my guidebook and guide to share the stories, but with the lens of hindsight, the internet, and the information I absorbed while visiting, let’s take a look at Petra through a happy lens of all three perspectives meshed into one… a lens where history, archaeology, and myth meet in a still partially unexplained ancient mystery.

T he views over the Petra Valley spread wide from my thin ledge at a small park in Wadi Musa, Jordan, the shadows accentuated the towering height of the rocks. Just minutes into our Petra journey and we we’re already confronted with one of the myths suffusing the ancient city. We planned to stay overnight in Wadi Musa, a small tourist town and the gateway to Petra. The name Wadi Musa means “the Valley of Moses” and this town, which stands high above Petra, shoulders a tenuous connection to the biblical past.

They allege that somewhere in that tangled maze below my ledge, that Moses struck a rock to bring forth water to the Israelites. The tale holds only possible truths, but no matter the veracity, that story forever linked Moses to this imposing sight… and you can bet that was a job well done for the Crusaders, who had no idea this city would last for so long. They had no idea the wide-ranging impact their story would have on the modern development of the myth and lore of this ancient civilization.

My panoramic aerial views were just the beginning, however, and later that day we descended into the tall rocks to find the ancient pathways leading into Petra. It’s worth noting though, that unlike the epic descent of Indiana Jones into the ancient city, we took slower pace once inside the city. We shielded the bright sunlight with our red Jordanian keffiyeh and walked the wide streets as the horse-drawn carriages passed, laden down with the tourists unable to navigate the miles of rocky roads winding through the city.

Within minutes of entering Petra, the first examples of rock-carved architecture danced to life from the sandstone and the precise, sharp lines jutting from the pale rocks could have been sliced from the rock a hundred years ago, instead of two thousand years ago.

I looked at those rocks with a snap of realization… this day at Petra isn’t akin to walking through a museum, with its carefully displayed information and artifact-filled glass domes. No, Petra was once a thriving city and a hub on the caravan trade route, meaning the city holds miles of roads, paths, and structures, each piece of their civilization is still standing in its original spot, open to the elements and to the imposing blue skies.

Well, blue skies for a bit, at least. The white sunshine dimmed as we entered a deep cleft in the rocks, narrow and tunnel-like, the sun was a mere blip overhead, sprinkling sunlight into the cracks as my eyes darted upward toward the patches of blue.

As we progressed through the city—our pace was slow as we photographed, examined and learned about each nuance—the passageways unfolded on a grand scale. The size dwarfed us into nothing more than small ants scurrying between the rocks, the walls were imposing in their stark rise from the sandy floor. When I was inside the rock passageway leading to the Treasury I was a mere speck compared to the soaring height surrounding me; the walls loom overhead, their smooth surface belying the ancient earthquake that likely ripped the rocks apart and formed the chasm we walked through to find more of Petra’s iconic carvings.

The scope and size of these walls loomed over me as we walked and tiny licks of claustrophobia creeped in until we entered a small open courtyard.

This courtyard marked the beginning of many of the better preserved carvings and I noticed a carved channel gently slopping downward, descending with us deeper into the city. The shallow channel was a clever way for the Nabataeans to carry fresh water throughout the city and combat the dry, arid temperatures.

The desert climate is so seemingly inhospitable to a city-dweller like myself, and yet, like the Romans, the Nabatea created a rain-collection, storage, and transportation system that made this huge city an oasis in the middle of a seemingly stark, dry desert.

Unlike the Romans though, the Nabatea only left small clues about the whys and the how is they managed to pull off such a feat.

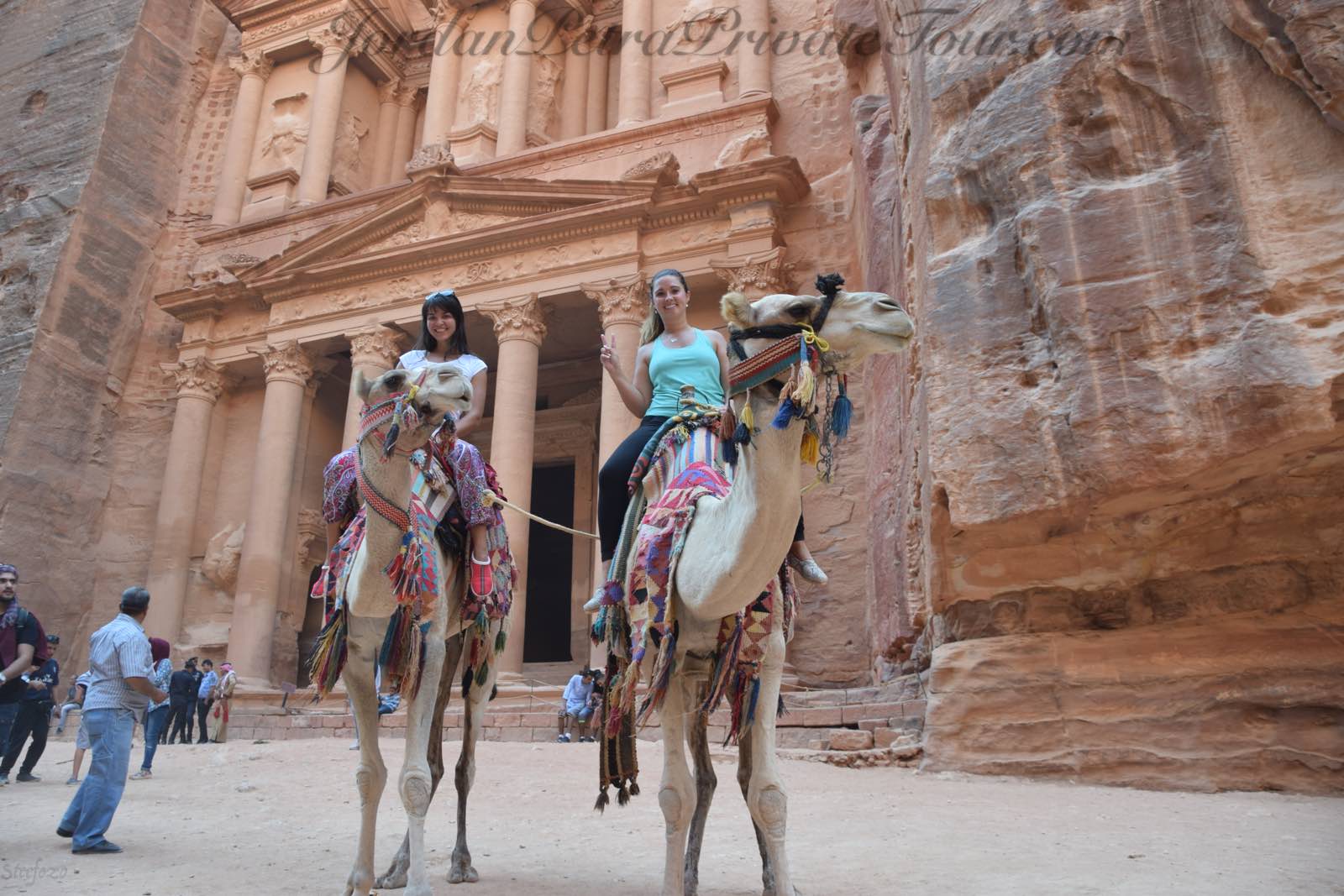

An hour after walking into Petra, I had finally penetrated the city deep enough to pass through the Siq, the last narrow and darkly lit pathway guarding the Al Khazneh, better known as the Treasury.

We left behind the intricate carvings in the courtyard and wound through the last bit. Ahead of us, a keyhole-like cleft in the rock teased me on approach and showed the first glimpses of the tall columns and carvings on the Treasury.

The structure was taller than I imagined, and more detailed. Likely carved around 100 B.C.E., the details still etched into the soft sandstone rock speak to why so many myths and stories circulate today. Is there a bounty of treasury hidden under this carved rock?

Some Bedouin through the decades have believed this story and the pockmarked surface from gun shots aimed at the upper Urn speak to a shared yearning and dream for undiscovered treasures.

Archaeologists discount claims that the Treasury’s elaborate facade was built to house the booty of an Egyptian Pharaoh, instead research proved the urn on top is completely sandstone, not hidden treasure. The historians counter that the Treasury is, like many of the other huge sandstone facades, a colossal burial tomb.

Little is actually known about the Nabataean though, so in my mind I looked at smooth columns and eroded statues and imagined the mythological gods and goddess that once adorned the surface.

These imagined symbols of Nabataean faith would have jutted life-like out of the sandstone and then journeyed through the day as a riot of colors matching the sun’s movement across the sky. Rose-red in the soft morning light would give way to yellows and browns in the harsh light of midday before a burnt, deep orange would settle over the sandstone gods as the sun took a final bow to the creative imagination and skill of the Nabatea.

Once impressed with these first sights of Petra, and the fanciful imagining of gods that may have never existed, the path curved a bit onto the Street of Facades. Or rather, a parade of carved out tombs, that pale in individual comparison to the Treasury, but when viewed in succession they are gorgeous in their own right.

Though many view the Treasury as the price of admission, Petra was once an expansive city. Our wanderings had only warmed us up for the rest of the journey.

We entered the heart of the city, and I was struck with awe as a wide expanse of what was once a bustling city opened up before me.

Dark black holes dotted every rock wall within sight. The view spread to miles and miles of sandstone rocks, enough housing hidden inside the rock to hold thousands.

Like most cities, the large Roman-style amphitheater sat prominently within the center of town, facing yet another huge wall of tombs rising out of the rocks; at least that’s the best guess. Without written documents from the time, historians can only assume this is how the people of the city lived and flourished. Petra remains a bit of a mystery and the Nabataean continue to closely guard their secrets for perhaps another millennium.

Examining the details showed layers upon layers of tinted sandstone, the ribbons of red, orange, yellow and brown creating distinct patterns on the columns and tombs. In fact, it is exactly this inherent quality unique to sandstone that lends these tombs and facades such a regal elegance and lasting beauty.

No paint, design, or ornate intricacies could have ever matched nature’s paintbrush for this ancient site.

I may have been hiking modern paths carved into the desert for tourists, but the curve of the current roads echo the same streets that bore the camels and caravans populating our ancient stories, myths, and religious texts.

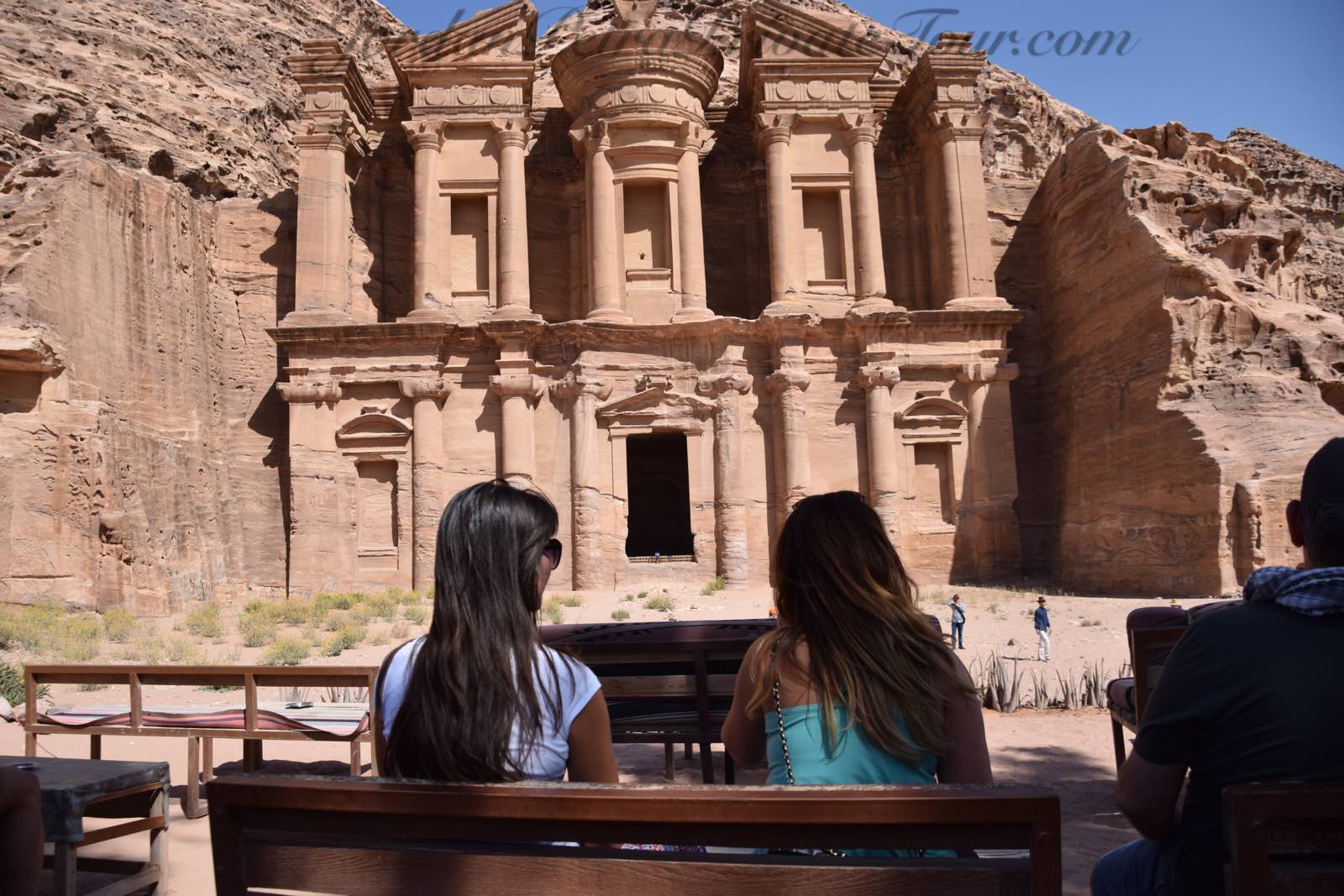

Capping off the day of poking around Petra’s ruins was a hike to the Monastery, Ad-Dayr, which was placed high on a mountainside carved deeply into a raw wall of rock. Though not as touted as the Treasury down below, the Monastery better showed the grand scale of these structures that were carved right out of the side of tall, sheer mountains.

The Monastery, likely also a tomb but re-purposed by the Crusaders and those later in history, sat tall and proud against the cerulean sky the day we visited.

We sipped cold lemon drinks in the shade as we took in the view and again I was left wondering how the soft sandstone stood for thousands of years. The pillars on the facade are smooth and silky from afar because of the ribbons and layers of sandstone carefully carved two thousand years ago.

It’s hard to imagine these structures were ever more impressive than they are now, is it even possible they possessed more natural beauty at the heyday of the Nabataean civilization?

After leaving the ancient city and looking out over the Petra valley for a sunset from Wadi Musa, it was easy to see why the city has inspired centuries of myths and legends.

In the face of little hard data, our collective romanticism creeps in and we as a modern society are instead free to imagine the daily lives of the Nabataea. Their fights against the Romans, another powerful ancient civilization, for control; the shifting power at this central post in the epicenter of our cultural history.

This region is considered the cradle of civilization and looking through the complexities of Petra, the biblical stories that played out in the deserts and plains, it’s easy to let imagination take flight and fancy some of these myths and legends just might possibly be true.